|

William Seymour is with the Sons of Confederates, Camp No. 1202. From March 28 to May 14, 1862, Tucson was under the Confederate flag.

Photos by David Sanders / Staff

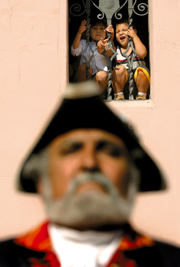

Jessica Ramirez, 4, and brother Jesús Manuel, 3, sneak a peek at Tony

Urias, dressed as a 1775 presidio guard.

By Ernesto Portillo Jr.

Imagine for a moment that day 227 years ago when Col. Hugo O'Conor rode up the

Santa Cruz River from Tubac to find a new settlement for the Spanish crown.

He, his small group of soldiers and Padre Francisco Tomás Gárces arrived near today's old Pima County Courthouse.

It had to have been hot and

muggy. The settlers likely were wearing heavy leather and wool clothing.

Dismounting to rest their rumps after the 40-mile trek, their first words probably went something like this:

"Darn, the roads are bad around here," a frustrated one says. To which an optimist replies, "Yes, but now that we're here, we'll fix the roads. Just wait and see."

I imagined that conversation Tuesday at the courthouse as Tucson celebrated its birthday.

The many flags that have fluttered in our dry winds during the two centuries and more since then passed by the courtyard.

A proclamation by O'Conor, establishing El Presidio de San Agustín del Tucson, was read in Spanish and English.

The hour-long ceremony was a reminder of our local history, as recorded by the European newcomers.

But not everything was written down. Someone needs to fill in the blanks.

I wondered what the soldiers and the Franciscan priest said as they scouted the east bank of the Santa Cruz River.

They weren't the first to come here, of course. The O'odham, whom the Spaniards called Pimas, lived in villages scattered around the base of the black hill from which Tucson gets its name - Chuk Shon.

O'Conor and company weren't even the first Europeans to arrive. Padre Eusebio Kino, a Jesuit, came 80 years earlier and called the place San Cosme y Damien de Tucson.

I imagined O'Conor and his troops admiring the crops grown by the first inhabitants using the waters of the Santa Cruz. They probably said, "Gee, this looks like a great place to live. We'll always have a source of water in this dry desert."

O'Conor wrote that the availability of water was one of the critical factors in establishing a garrison in an area now surrounded by Main, Pennington, Washington and Church streets. The other reasons he cited were "pasture and wood."

O'Conor was ancestor to developers who now sell Tucson to outsiders by promoting the illusion that it has an abundance of water and open space.

But the Irish-born O'Conor was more than an 18th-century land speculator. He was a champion of diversity.

He spoke English or Gaelic, or both, and he led a group of Spanish soldiers, some of whom spoke Catalán, into the land of the O'odham language.

I could hear O'Conor saying in Spanish to the ancestors of today's Tohono O'odham: "From this day forward, everyone will learn and speak the language of the Castilian crown."

Of course, he couldn't predict that 225 years later Arizona voters would pass Proposition 203 banning Spanish instruction in public schools.

How could O'Conor have imagined any of what his presidio would become - a metropolis five times more populous than the Dublin of his day.

Still, O'Conor the soldier might have had a bit of the soothsayer in him, proclaiming as he did that the new presidio "effectively closes the Apache frontier."

We've been closing frontiers here ever since.

* Contact Ernesto Portillo Jr. at 573-4242 or netopjr@azstarnet.com.

He appears on "Arizona Illustrated" on KUAT-TV, Channel 6, at 6:30

and 11:30 p.m. Fridays.