Chapter One: City a vital link in drug trad

Today, the Arizona Daily Star looks at how much money Tucson makes by receiving, repackaging and distributing loads of pot to the rest of North America. On Monday, the Star shows how a local marijuana ring was unraveled by a single informant. Tuesday, local leaders discuss how the trade affects us and whether to consider stricter drug enforcement, more emphasis on treatment, or legalization.

By Tim Steller

Arizona Daily Star

December 8, 2001

http://www.azstarnet.com/stashcity/

While every major city has a retail drug trade directed at consumers, Tucson supplies all of them.

Take, for example, David Harvan's case. In the late 1980s and early 1990s, Harvan came to Tucson about 25 times to buy and send loads to Virginia.

"In Tucson, there was tons of marijuana sitting here on any given day," said Harvan, of Bisbee. "Sometimes we'd go see four or five loads in an afternoon. It was just like shopping."

Harvan pleaded guilty to marijuana trafficking and spent more than two years in state prison. The former electrician returned to Bisbee to re-launch his brewery, Electric Brewing.

"In Tucson, there was tons of marijuana sitting here on any given day. Sometimes we'd go see four or five loads in an afternoon. It was just like shopping. "

David Harvan, former drug trafficker

Investigators say there has been even more marijuana passing through the city in recent years.

"Historically, there have been connections between people in Southern Arizona and people in Mexico in the marijuana distribution network. Over time that's just grown," said Raymond L. Vinsik, director of the Arizona High Intensity Drug Trafficking Area, a federal intelligence and anti-drug coordinating center known as HIDTA.

Traffickers working here spend money like anyone else - on business and personal costs such as housing, vehicles and food. They earn that money by marking up the price of each marijuana load to cover expenses and make a profit.

Take the case of William S. Fusci, a Tucson man who has acknowledged being a link in the chain of the local marijuana economy and is scheduled for sentencing Dec. 21.

Drug Enforcement Administration agents investigating Fusci last year found that for one 400-pound load he paid $550 a pound to a Tucson supplier, according to federal court documents. When Fusci sold marijuana to Robert R. Boswell in Florida, he usually charged about $1,000 per pound, Boswell said in a plea agreement this year. The difference, in this case $450, is the Tucson distributor's markup.

In his plea agreement, Boswell, who is scheduled to be sentenced Monday for conspiring to distribute marijuana, acknowledged buying around 5,000 pounds of marijuana per year from Fusci in recent years. Fusci, 41, distributed pot loads for nine years, according to the indictment against him.

"While we're pending sentencing, there's nothing we can say," said Fusci's attorney, Mike Bloom.

Law-enforcement records show that in 2000, officers seized 291,994 pounds of marijuana in Tucson and Southern Arizona areas that feed into the city, from Douglas to the Tohono O'odham Reservation.

Drug investigators don't know what percentage of total traffic they seize, but they estimate the top possibility at 20 percent. Using this estimate, 1.17 million pounds of marijuana made it to the Old Pueblo in 2000.

At a markup of $300 per pound, an amount suggested by interviews with five traffickers, investigators and court records, Tucson made $350 million on wholesale marijuana sales last year.

Click on graphic to enlarge

Changing the percent seized or average markup yields a broad range of marijuana-related revenues, from as little as $88 million to as much as $1.3 billion.

Add to that the approximately $75 million the federal government spent locally in 2000 on agencies partially or wholly dedicated to fighting drugs, and marijuana distribution rivaled the optics industry. Optics firms, working to earn Tucson the title "Optics Valley" with products from headlights to telescopes, made about $650 million last year.

"Brand-new, fresh dollars"

At around $350 million in revenues and $75 million in federal expenditures, marijuana added 2 percent to the area's total personal income of $20.7 billion in 2000.

"That's pretty large," said UA economist Marshall Vest. Since most of the marijuana that moves through Tucson is distributed to the rest of North America, Vest said, "It represents a flow of brand-new, fresh dollars into the community."

Economists calculate the spinoff effects of legitimate industries by looking at the jobs and wages created when employees spend money in the community. This "multiplier effect" would be impossible to determine with marijuana distribution, said Vera Pavlakovich-Kochi, program director at the University of Arizona's Office of Economic Development. The reason: No one can track how much marijuana money stays in the area.

A study Pavlakovich-Kochi conducted in 1997 provides a clue. She looked at the economic impact of the fresh-produce industry on Nogales and Rio Rico. The marketing services segment of the produce industry - the sector that mirrors the role Tucson plays in the marijuana industry - generated $376.4 million, which created a multiplier effect of 6,052 jobs and $159 million in wages.

No direct comparison can be made between Nogales-Rio Rico produce marketing and marijuana distribution in Tucson, she cautioned. Still, she said, "definitely there is an impact on the economy. There is no doubt about it."

The beneficiaries of the marijuana trade, most of them unknowing, range from "real estate agents to car dealerships to titling companies," said Pennie Gillette, an Arizona Department of Public Safety lieutenant who directs the Arizona High Intensity Drug Trafficking Area intelligence center here.

Those in the hospitality industry also get an added boost from traffickers' frequent meetings.

"When they meet," said Vinsik, Gillette's supervisor at Arizona HIDTA, "they want to meet at fancy hotels and have fancy dinners and negotiate their deals."

Capitalizing on Mexico ties

To understand why the money flows to Tucson, look south.

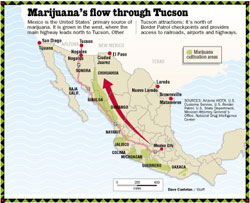

Mexico is the United States' top supplier of marijuana, probably accounting for more than half of what Americans consume, said Matt Maggio, chief of the national drug threat assessment unit at the National Drug Intelligence Center in Pennsylvania.

Mexico's top marijuana-growing states are primarily in the west, including Sinaloa and Jalisco. From those states, the most direct land route north to the United States is Mexican Highway 15, which ends in Nogales. The Arizona border town of 21,000 residents could function as a marijuana distribution center, but Tucson, just 60 miles away, serves the traffickers' purposes much better.

Tucson is big enough and diverse enough that traffickers fit in without drawing notice. It's north of the U.S. Border Patrol's checkpoints and offers access to roads, rail lines and airlines.

Marijuana owners in Mexico take advantage of Tucson's location, as well as family and business connections to Southern Arizona, said Ron Benson, a Pima County Sheriff's Department lieutenant who until Oct. 21 was deputy commander of the Metropolitan Area Narcotics Trafficking Interdiction Squads, or MANTIS.

"It's not unusual to have the kingpins in Mexico, and their managers be up here in Tucson," Benson said. "It's the job of the managers to bring the stuff together and parcel it out to their buyers."

Traffickers deliberately break the journeys of their marijuana loads into separate legs to conceal the identities of the participants from each other, drug investigators and traffickers said.

It's just like dealing with any kind of commodity in private industry. You come here and you're going to get a better price. That's worth the risk of transporting it back to wherever and selling at a markup.

James A. Woolley, assistant special agent in charge of the DEA's Tucson office.

This "compartmentalization" offers security and creates more links in the economic chain, offering more people opportunities to profit.

In Mexico, drivers or pilots take the harvest to a staging area near the U.S. border. Several organizations are dedicated to taking the loads from Sonora into Arizona.

One method of choice is by car or truck, through official ports of entry, where their purpose is masked by the volume of traffic or facilitated by corrupt officials. Another favored method is to cross at out-of-way points between the ports of entry, on the backs of human "mules" or in four-wheel-drive vehicles.

Federal drug-fighting efforts at the border make the trip more dangerous for the haulers, but it's a short trip. The loads are dropped on the Arizona side, where a new driver will bring the pot to Tucson.

71 stash houses

Daniel L. Otero of Tucson used to make those drives, he acknowledged in a federal presentence report. From December 1998 through April 1999, Otero picked up three loads of marijuana at a spot near Parker Canyon Lake, about 14 miles southwest of Sierra Vista.

He drove the loads, which totaled 1,878 pounds, to stash houses in Tucson, the report says. He also drove a load to Phoenix. For his efforts, Otero was paid about $35,000.

Otero, 49, admitted conspiring to traffic marijuana and was sentenced to 6 years, 3 months in prison.

He said his boss was Tucson businessman Guillermo M. Lechuga, the report says. It's an accusation Lechuga is still fighting 2 1/2 years after marijuana trafficking charges were filed against him.

From January last year through October this year, drug-trade investigators found 71 stash houses in the metro area, each containing 100 to 7,000 pounds of marijuana, according to data compiled by Arizona HIDTA.

Tucson's rival as a stash-house center, drug investigators said, is El Paso, where agencies have a task force dedicated to finding the houses, said Robert Almonte, deputy chief of the El Paso Police Department. Investigators there found 89 stash houses during a period when 66 were discovered in Tucson, which has no task force.

The people guarding stash-house loads are another link in the chain of Tucson's marijuana economy.

In Otero's case, the stash-house sitter was his son, Daniel A. Otero. The younger Otero said he was not paid directly for living at his stash house, in the 1300 block of North Apache Drive, behind the Arizona Schools for the Deaf and the Blind, according to a presentence report. But his father paid the younger Otero's rent and living expenses.

The Otero family declined to comment for this story.

Another Tucson couple accused in the Lechuga indictment told investigators they stored four loads of marijuana in their garage, in the 2900 block of West Camino Camelia. Bernice and Valentin Villa said they were paid $10 per pound for allowing a total of 2,100 pounds of marijuana to be kept there for a few days each, between 1997 and 1999, according to a federal presentence report.

Valentin Villa "stated he became involved with storing the marijuana purely out of greed as he and his wife did not need the extra money," the report said. Both pleaded guilty to possessing 150 pounds of marijuana with intent to distribute and were sentenced to five years probation.

"They're interested that other people don't make the same mistake," said the couple's attorney, Robert Nelson. "The legal costs and the ramifications of the criminal conviction were far more costly than any monies obtained by their poor judgment."

Stashed in your neighborhood

There was a time when people living in the more affluent sections of Tucson could consider marijuana the problem of other neighborhoods. That time has long since passed, said Francis Karn, who spent 20 years working drug enforcement in the Tucson area before retiring in 1998.

"When we first started, most of the stash houses were down on the Southwest Side, and when I left, they were all over the city," said Karn, who was president of the Arizona Narcotics Officers Association in 2000. "We took several houses out up in the Foothills."

In the last two years, most of the stash houses that drug investigators have found were in neighborhoods alongside Interstates 10 and 19. But eight were also on the far East Side and in the Foothills. On Saturday afternoon, MANTIS officers went to a house near the corner of East Orange Grove Road and North First Avenue and discovered more than a ton of marijuana.

Last year, they found a big load in the 6700 block of North Nanini Road, the only rental home on a street just east of North Oracle Road, where the average home value is about $260,000. On Nov. 9 last year, drug investigators were watching from a neighboring yard when a volunteer ambulance from Alaska pulled up to the house.

MANTIS officers served a search warrant and found 2,790 pounds of marijuana in the master bedroom closet. Neighbors said they noticed almost nothing unusual from the house until the day of the raid.

"It was just a little excitement is all," said neighbor Russ Tarvin, who allowed investigators to hide in his yard. "We had no clue."

That's the idea of a stash house, traffickers and investigators said.

"If it's a sophisticated organization, they might have a ground team that comes in and sets up all the stash houses," said DEA spokesman Jim Molesa. "They're responsible for the legitimization of these houses within the community, then they're gone."

Harvan, the former trafficker from Bisbee, said Tucson stash houses he visited all looked, from the outside, like any other house in the neighborhood. Inside, however, they were different.

Click on graphic to enlarge

"There wouldn't be any furniture or anything. There would be a bunch of guys hanging out, and then in the bedroom there would be a ton of marijuana or something," Harvan said.

Traffickers prefer rentals, so if an operation is busted, the government can't seize the homes and sell them, traffickers and investigators said. And for the same reason they're popular with families carting armloads of groceries, attached garages are preferred by traffickers.

Neighbors may notice the drapes are pulled all the time and foil may cover the windows. Sometimes, the only vehicles that stop at a stash house are pickups and sport utility vehicles with either Mexican, East Coast or Midwest license plates. The house may seem abandoned or very lightly lived-in, with occasional high traffic.

Traffic gave away a stash house in the 6200 block of East 26th Street, where investigators found 472 pounds of marijuana June 20.

"We knew there was something going on," said neighbor Roy Jackson. "In the last few days it was one car after another."

Final link in marijuana chain

Usually, the landlord has no knowledge of the illegal purposes of tenants who are stash-house operators, drug investigators said. But in one recent case, authorities accused the landlords of being active participants.

In January 2000, MANTIS officers were investigating a ring of Jamaican marijuana traffickers operating here when they seized 1,500 pounds from townhouses in the Belle Vista development near East Speedway and North Camino Seco. That led to an undercover operation against the owners of several rental townhouses, according to an affidavit filed by Tucson police Officer Roger Nusbaum.

Late last year, owner Gregory T. Shepis began renting to undercover MANTIS agents who said they discussed with him their need to store loads of marijuana, according to an indictment issued by a Pima County grand jury.

The agents said they showed Shepis, 64, a load of 214 pounds of marijuana stored in one of his units and gave him a pound of pot in place of a security deposit, the indictment says.

Shepis and his wife, Michelle, are facing trial Feb. 12 on felony charges, including marijuana conspiracy and money laundering. Both deny the charges.

Gregory Shepis' attorney said the undercover officers, who wore recording devices during their conversations with Shepis, entrapped him. The attorney, Stanton Bloom, said Shepis charged the usual rent to the undercover officers and made no additional money from their supposed marijuana trafficking.

Added Michelle Shepis: "I certainly would never have rented to anybody if they were in any way bad. If they're going to set you up, they're going to set you up, and they're not going to tell you till it's too late."

When the marijuana arrives at Tucson stash houses, the suppliers either send it directly to a regular customer or must find a buyer. That's where another link in the economic chain steps in - deal- makers who know the haunts and personalities of the local drug trade

DEA agents arrested one such deal-maker, Jorge Zuniga, last year in their investigation of the ring led by Tucson distributor Fusci. Zuniga arranged a 230-pound marijuana sale to Fusci, DEA agent Timothy Bartels said in a criminal complaint. For connecting the supplier and buyer, Zuniga received $25 per pound, or $5,750, Bartels said.

Zuniga pleaded guilty Nov. 6 to conspiring to possess marijuana with intent to distribute.

The final link in the Tucson chain is the distributor, who may be connected to a Mexican organization or may have a separate group. The Tucson distributor usually makes in the range of $100 to $500 per pound, investigators and traffickers said, but takes whatever price the market will bear.

"It's just like dealing with any kind of commodity in private industry," said James A. Woolley, the assistant special agent in charge of the DEA's Tucson office. "You come here and you're going to get a better price. That's worth the risk of transporting it back to wherever and selling at a markup."

Business of drug interdiction

During the 25 or so years since Tucson became an important player in the international marijuana trade, the city has also become a drug-war nerve center. A Star analysis of federal agencies involved in drug enforcement found they spent about $75 million in Tucson during the fiscal year that ended Sept. 30.

About three-quarters of the convictions they produced were marijuana cases, according to Arizona federal court figures. Tucson's federal court saw 976 drug cases in the year ending Sept. 30, 2000.

Anti-drug agencies such as the U.S. Customs Service and DEA have large offices here, focused primarily on drug investigations. A typical special agent makes at least $60,000 per year.

But the federal agency here that makes the most marijuana seizures is the Border Patrol, which has a station on East Golf Links Road and a sector headquarters on West Ajo Way. The primary duty of that agency is to enforce immigration laws, but the agents work between ports of entry where marijuana loads often cross the border.

The Border Patrol spent more than $23 million on its Tucson offices and employees last year.

Federal tax dollars also flow here to lesser known anti-drug agencies.

There's the Arizona High Intensity Drug Trafficking Area, a secretive body with a $12.4 million budget. HIDTA has a large, unmarked building near Tucson International Airport, where 240 people work.

Many of them are intelligence analysts, some with CIA-level security clearance. Others are officers from agencies as diverse as the Tucson Police Department, the Arizona National Guard and the FBI, working together in a variety of task forces. That blending is meant to break down the traditional rivalries between agencies.

"Our job is to make people want to work together, and the carrot, of course, is the money," Vinsik said.

Another little-known agency is the U.S. Customs Service Air Branch, the largest operation of its kind in the country and based at Davis-Monthan Air Force Base. It helps track smugglers on the ground along the border, conducts surveillance above Tucson and pursues suspicious cross-border flights, even across state lines.

Customs has 80 employees at the Tucson air branch, 60 of them pilots. Another 70 aircraft mechanics, employees of private contractors such as Raytheon, work at the air branch repairing Blackhawk helicopters and other aircraft.

The 60 pilots make about $75,000 per year, said Dennis Lindsay, chief of the Tucson air branch.

"Tucson is a major player in drug interdiction," Lindsay said.

It's all business

When drug investigators seek out local links in the marijuana chain, they often find business owners.

Take Guillermo M. Lechuga. Accused of running a major marijuana network, Lechuga is also the owner of a Tucson business approaching its third decade - Superior Natural Oils International. SNOI, in operation since 1983, produces jojoba oil and other products and sells them to cosmetic companies around the world.

DEA agents arrested Lechuga on April 13, 1999, and he was indicted along with 42 others on charges he operated a continuing criminal enterprise and committed five related crimes. He has pleaded innocent and is fighting to suppress evidence that investigators obtained through wiretaps of various phones, including one at SNOI.

After his arrest, Georg Hieber and Edgar Zastrow, German customers of SNOI, wrote a character reference for Lechuga, calling him a "serious, reliable businessman" who "kept his promises."

At the time of his arrest, Lechuga employed about 10 people at the company's office, 2555 N. Coyote Trail, just off West Grant Road, according to court documents filed by his attorney, Alfred "Skip" Donau. Lechuga employed others at fields near Guaymas, Sonora, and at a processing center in Nogales, Sonora.

Lechuga paid his Tucson employees close to $400,000 per year in salaries, Donau wrote, and the company grossed up to $6 million. Now out on bond, Lechuga continues to run the company.

According to a sworn affidavit, DEA agents suspect Lechuga was in the marijuana business even before he got into natural oils and that he used SNOI as a front. The DEA's first record of Lechuga is from 1975, when he was arrested in Phoenix in possession of 400 pounds of marijuana, but the charges were dropped, DEA agent Tracy Donahue said in an affidavit.

"I don't think there's any credible evidence it was used as a front," Donau said of the company. "I know that's not the case, or they (federal prosecutors) would be seeking forfeiture."

Whatever the source, Lechuga amassed enough money to own a house on North Casas Adobes Road worth around $500,000, according to the Pima County Assessor's Office. The federal government is seeking to make Lechuga forfeit that house, as well as about $400,000 in bank accounts and two Land Rover SUVs that the goverment claims were bought with the proceeds of marijuana sales.

Some traffickers, like Tucsonan Jose Luis Arevalo, own companies that exist only on paper. Arevalo was convicted in Tampa, Fla., last year of conspiring to traffic marijuana and launder money.

During the trial, prosecutors presented a flow chart of the companies he ran. It included three companies dedicated to real estate, as well as a storefront business, Burrito Bandit, that operated at 8320 E. Broadway in 1990 and 1991.

How much money went through Arevalo's companies is unknown. But a DEA analyst explained six months worth of drug ledgers at Arevalo's trial, federal prosecutor LaTour Lafferty said, and the jury reached its own conclusion: $17.25 million in half a year.

Arevalo's attorney, Frank Rubino, disputed that figure.

"That was what the government believed was the gross amount of the (marijuana) value in the indictment. Nobody got that money, because it didn't exist,," Rubino said.

Despite the huge sums, most of the money made on the marijuana that moves through Tucson does not stay here, drug investigators said. A Tucson distributor who sells marijuana for $1,000 a pound in Michigan may have to pay $600 per pound of those proceeds to his supplier in Mexico.

"The bulk of it is going back across the border," said Bill Dickinson, chief of the Pima County Attorney's Office narcotics division.

Plus, offshore banks provide an anonymous and attractive shelter for illicit earnings.

Money laundering within Tucson is on a small scale, usually through businesses even smaller than Lechuga's, Dickinson said. Laundering can keep small businesses afloat and add to corporate income taxes.

Trafficking suspect Mark E. Steele owned Alejandro's, a popular Downtown restaurant, from December 1994 until May 2000, according to city records.

After five years as a fugitive, Steele was arrested in June on a charge of possessing marijuana with intent to distribute. After his arrest, the only income Steele listed on a financial affidavit was $30,000 from the sale of the restaurant.

Steele's attorney, Sean Bruner, said Steele pleaded innocent. He is asking that the case be combined with a related case filed against Steele in Cleveland.

"Often what they do is have a business that is probably marginal," Dickinson said. If the traffickers own a pizzeria, they'll put the drug proceeds into the business "so that the pizza place looks like it sells a hundred pizzas a night when it only sells 10."

Big money. This is the formula we used to calculate Tucson's marijuana revenues.

291,994 x 5

= 1,459,970 -291,994 =1,167,976 x $300

Pounds of marijuana were seized in 2000 in Tucson and the border region that feeds it, from Douglas to the central Tohono O'odham Reservation. Investigators believe they seize at most 20 percent of the marijuana that crosses the border. This is the amount that would have crossed into the region that feeds Tucson had there been no seizures. This is the amount seized that did not make it through Tucson. This is the number of pounds that made it through Tucson that year. This is an average markup that Tucson traffickers add to the cost of each pound of marijuana they distribute to the East and Midwest.

=$350,392,800

This is the revenue Tucson traffickers make for their marijuana sales to the rest of the country. It is not all profit, since the markup must cover some costs, such as paying drivers.

* Contact Tim Steller at 434-4086 or at steller@azstarnet.com.

------------------------------------------------------------------------

All content copyright © 1999, 2000, 2001 AzStarNet , Arizona Daily Star and its wire services and suppliers and may not be republished without permission. All rights reserved. Any copying, redistribution, or retransmission of any of the contents of this service without the expressed written consent of Arizona Daily Star or AzStarNet is prohibited.